Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

Relations between employers and workers in the slate industry have long been most cordial. The most recent demonstration of this is the co‑operation of the North Wales Slate Quarries Association ‑ a new Employers' Association formed in 1943 ‑ and the North Wales Quarrymen's Union in the revived Welsh Sectional Industrial Council for the Slate Quarries Industry which held its inaugural meeting in November, 1943. Industrial relations were not always as happy as they have been during the past twenty years, and our survey of the .expansionist period in the history of the industry would be incomplete without a brief account of the great industrial disputes in the early 'seventies of the last century, when the men struggled for recognition of their Union by the employers.

The Penrhyn Quarry was the arena where the first round between employers and workers was fought. In that quarry in the 'sixties the quarrymen were complaining of low wages, great inequalities in wages, corrupt practices and favouritism. In 1865 the men elected a committee to approach the management with a view to removing these grievances, but getting no satisfaction they came out on strike on the last day of July, 1865. They applied to the proprietor for an interview, and this was granted, and upon his promising to redress their grievances the men at the end of a fortnight returned to their work. These promises remained unfulfilled, and the men decided to form a Union; this was started in November, 1865, and some 1800 of the workmen joined. On December 2nd, 1865, Colonel Pennant caused a printed notice to be circulated among his quarrymen cautioning them to avoid having anything to do with such a movement as a Trade Union in the future as on the very first rumour of such a state of feeling, he will immediately close the quarry, and only re‑open it and his cottages to those men who declare themselves averse to any such scheme as a Trade Union." The quarrymen decided to give up the Union, but as a forlorn gesture 1,230 men signed a protest against a portion of the circular which described the appointed delegates as "agitators," but declared that they had "entirely renounced the idea of a Trade Union trusting that Colonel Pennant will act according to his promise that there will be no more severity or revenge*. In this way the first attempt to form a trade union fizzled out.

The inability of the slate quarrymen to form an effective union during the first three‑quarters of the nineteenth century is not surprising. Any succesful movement towards combination would have to begin in one of the larger quarries, but there were special reasons which made it difficult to start any such movement. It must be remembered that the management of the quarries, although despotic, was in many ways most benevolent Lord Penrhyn, for instance, had built and equipped an excellent hospital for his men and contributed £200 annually towards the Quarry Club. He provided coffins for all his tenants and workmen when they died and gave small pensions to the widows of workmen killed in the quarry. Men who had grown old in his service were pensioned ‑ scores of old men and injured workmen, who in other occupations would have been thrown on the industrial scrap heap, were paid for doing light work in the quarry. The majority of his workmen lived on his estate; he granted them building plots at low ground‑rents and upon expiry of the leases the cottages were let at extremely low rentals. He built National Schools and churches; his wife contributed lavishly towards clothing funds for the children and founded the first Friendly Society for women to be established in North Wales. The same things were true of several other large quarry proprietors.

There was also lacking any strong feeling of solidarity among quarrymen as a class. The slate districts, although in close geographical proximity, were divided from each other by mountain barriers; means of communication between them was exceedingly poor until the 'seventies, and each formed a distinct community having little social intercourse with the other areas. The movement of quarrymen from one district to another in search of work was sometimes bitterly resented, especially during slack times. Even the men who worked in the same quarry were drawn from wide and scattered areas; many of them had tiny farms and supplemented their wages by tilling little plots of land. Drawn from scattered areas and living under rural or semi‑rural conditions the quarrymen had more faith in the heroic creed of self‑help than in the newfangled ideas of collective action. The Welsh quarrymen possessed a full measure of the Celtic lavishness and cared a great deal for the welfare of his immediate friends and neighbours but little for his fellow workmen in a neighbouring quarry, or in another quarrying district. When the Penrhyn quarrymen endeavoured to form a trade union in 1865 it was strictly upon a company basis, and other quarries were urged to form their own unions Another potent cause of the industrial weakness of the quarrymen was - as has already been pointed out in a previous article ‑ the wage system peculiar to the industry.

Another profound influence was that of the Chapel and Sunday School,. Together they absorbed the quarryman’s mental energy and supplied them with a means of self‑expression. They inculcated into him the duty of obedience to one's worldly master and caused him to regard the miseries of this world as of no real significance. In the 'forties and 'fifties no Nonconformist was allowed to belong to a trade union. Nonconformity, particularly during the first half of the century, acted as a conservative force and militated powerfully against industrial strife; it did, however, provide a training in democratic government and the quarrymen's leaders during the late 'seventies were almost without exception Nonconformist deacons.

The unquestionable hostility of the quarry proprietors towards combination among the men was, of course, the most powerful deterrent. The management of the quarries was autocratic and any man who proved too independent in spirit was promptly dismissed, and in the Bethesda and Llanberis districts quarrymen were liable to be evicted from both their work and their homes.

There was among quarry owners in all districts an unwritten law that workmen discharged for their independent spirit were not to be employed in other quarries; this tacit agreement was strictly carried out until the exceptionally brisk state of trade in the ‘seventies so increased the demand for skilled labour that it became a dead letter. The 'black list" was an ugly phenomenon. In 1870, 80 workmen were dismissed from the Penrhyn Quarry ostensibly “because of slack trade"; it has surely some significance that these particular men played a prominent part either in the strike of 1865, in the attempt to establish a trade union in the quarry, or in the memorable election of 1868 when Colonel Douglas Pennant lost his seat to a Liberal candidate.

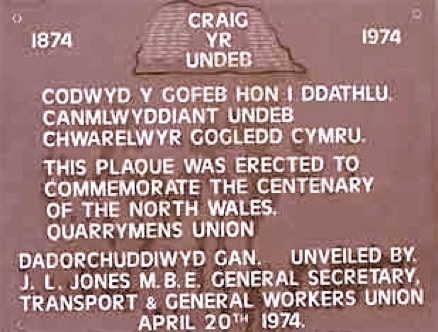

Despite these factors trouble was brewing in the early 'seventies. The cost of living was going up and wages were not rising commensurately. Many of the bolder spirits chaffed under the autocratic management of the quarries and the men who had been dismissed from the Penrhyn Quarry in 187o had found work in other districts, and their story had made a deep impression upon the quarrymen. Several writers to the local press advocated the formation of a Union. In December, 1873, the Dinorwic quarrymen chose a committee of fifteen to consider the feasibility of forming a Union and this committee met secretly each week at Cwmyglo. In January, 1874, this committee decided to form a Union for all the quarrymen of Caernarvonshire and Merioneth. No quarrymen were prepared to run the risk of becoming officers of the proposed Union, and so it was decided to consult several well‑known local gentlemen who had long interested themselves in their cause. The Union was to be called "The Society for the Defence of Slate Quarrymen," wishing to imply by its title that it was a purely defensive organisation and not a militant and aggressive trade union. The name of the Union was, however, within a few. weeks changed to "The North Wales Quarrymen's Union." The first official meeting was held on April 27, 1874, at Caernarvon and was attended by delegates from the four chief slate districts ' the election of the following officials was ratified: Richards, president; Hugh Pugh treasurer; J. O. Griffith, trustee; W. J. Williams, auditor; and W J Parry, general secretary. W. J. of Bethesda, proved to he an inspired organiser and within a few weeks lodges had been founded in most of the slate areas of North Wales.

The first conflict between men and the quarry proprietors took place in the Glynrhonwy Quarry, On May 21, 1874, Capt. Cragg, the manager, informed the men that they had to choose between the Union and their work. 113 out of the :it employed at the quarry chose the Union and they signed a bond binding themselves to defend their committee, and so they were locked out.

Three days later quarry proprietors held a meeting at Caernarvon in which eighteen concerns, including the Penrhyn and Dinorwic Quarries were represented. The following resolutions were passed

"(1). That this meeting has with great regret learnt that an attempt is being made by persons who have no connection with slate quarries to disturb the good feelings that have always existed between the proprietors and their men by establishing a Trade Union among the quarryman, the result of which is certain to be injurious to both masters and men.

(2). That, in the opinion of the meeting, every quarry proprietor in North Wales should refuse to employ any man who is ascertained to be a member of the Union, and that every proprietor or his representative should give notice of such determination to his men at the earliest opportunity..

(3). That the employers and their representatives present at this meeting

bind themselves not to take into their employ. any quarryman or labourer corning from another quarry without a written certificate from the manager or agent of the quarry he left."

Most of the quarry proprietors acted upon these resolutions, but a few others

such as Thomas Lloyd Jones and W. A. Darbishire, encouraged the formation of the Union. The demand for slate was so brisk, however, that the locked‑out Glynrhonwy quarrymen easily found work in other districts; within three weeks they were taken back as unionists, and great was among Welsh quarrymen.

June 4, 1874, Mr. Assheton Smith had announced that at the monthly letting of the bargains at the Dinorwic Quarries on June 18 the quarry would be opened only to non‑unionists. On the letting day the men chose the Union and 2,800 men were locked out. In the Dinorwic Quarries the men were satisfied with the wages and the management and the sole question at issue was the recognition of the Union. A deputation of the men met Mr. Assheton Smith and the manager, Col. Wyatt, and emphasised that "the Union had been established only for defensive and not for aggressive or political purposes, or

with any intention of interfering with management or agents, or internal mangements of the Dinorwic or any ther quarries in the County."

Mr. Assheton Smith was willing to accept a company union, to be called

“Dinorwic Quarries Union," of which he would be patron, the other officials to be chosen by the men from those connected with the quarry; for the purposes of this Union monthly subscriptions were to be collected to better their circumstances, assist or render assistance in cases of illness or infirmity and to assist widows and orphans. He refused to recognise the Union and the and men refused to consider his proposals for a company. union, which was nothing more than a kind of Quarry Club.

Quarry proprietors generally were convinced that the Union had been formed for political purposes by Liberals to wipe off the stain of the Liberal defeat in the county in the General Election of 1874. It was an undeniable fact that all the of the officials of the Union were active and prominent Liberals; the leaders among the quarrymen were Liberals, and the very few quarry‑owners who favoured the movement were Liberals. It was stoutly and emphatically denied, however, that the Union was a political machine," and it was pointed out that the movement had already been set foot by the quarrymen before W. J. Parry and the other gentlemen consulted and that the quarrymen themselves refused to become the officers in the Union as they feared dismissal from their work. An examination of their private correspondence and of the minutes of Union's meetings does not provide the slightest grounds for the accusation that the North Wales Quarrymen’s Union was formed for political purposes.

The Dinorwic proprietor in a few weeks signified his readiness to reopen the quarry if the officials of the union were chosen from among the quarrymen. The president and treasurer immediately resigned, and Mr. Smith conceded that W. J. Parry should retain his post as general secretary. The Union rules were modified so that all the officials, except the secretary were to be "quarrymen or persons engaged in or connected with quarries"; two new rules were introduced to the effect that no workman was to be molested for being a non‑unionist and that no further rules were to be adopted without notifying the quarry owners, and in the event of their objecting to the new rules the matter was to be referred to an umpire chosen by both sides. After a lock‑out lasting for nearly five weeks the men returned to work on July 20, 1874, having succeeded in persuading their employer to employ them as unionists.

Early in July the Penrhyn quarrymen had made a collection of £206 in support of the Dinorwic men; immediately this became known to Lord Penrhyn he caused the following notice, dated July 14, 1874, to be issued :

"Being informed that a large body of the workmen in the Penrhyn Quarries had given support to a Union formed at Llanberis for the purpose of dictating to the owners and managers how their quarries should be worked, I hereby give notice that I shall resist any such interference with the rights of proprietors of quarries, and shall, if such support be continued, immediately close the quarry."

This notice caused the men to flock to the Union and when the Penrhyn Lodge was established on July 20, its members numbered nearly 2,300. Unlike the Dinorwic quarrymen, Penrhyn workmen had serious grievances, and instead of waiting to be locked out they came out on strike on July 30, 1874.

Wages in the Penrhyn Quarry had for many years been lower than in almost any other quarry in North Wales. The highest wages in the industry were paid by the larger Festiniog slate mines; in those concerns in 1874 the average daily wage of the quarryman was 5s. 10d. and of the labourer 4s. 2d. In the smaller Merioneth concerns and in most of the Caernarvonshire quarries. the quarrymen earned on the average 5s. 0d. and the labourer 3s. 10d per day, and those were the wages ruling in the Dinorwic Quarry. Wages in the industry as a whole had advanced 12½ per cent. since 1865, whereas wages at the Penrhyn Quarry had fallen over the same period. There was an iniquitous system in the Quarry whereby all wages over £19 per month earned by a crew of quarrymen was appropriated by the management; this naturally caused the men to slack during the last week if they had earned that sum during the previous three weeks, and in effect it imposed a maximum wage of 4s. 0d. per day for quarrymen. Lord Penrhyn did not deny that the wages in his Quarry were lower than elsewhere, but maintained that following a tremendous fall of rock in 1872 the margin of profit had been very small, and furthermore, that his quarrymen enjoyed privileges which presumably were not enjoyed elsewhere. (In 1874 Lord Penrhyn was informed by his estate agent that he was making a profit of fourpence upon every shilling spent on working the quarry). The men contended that it was "neither just nor proper to expect the workmen to be satisfied with less than a proper day's wage for a proper day's work, because the work they are in does not return what the owner considers to be proper profit to him. . . . We are perfectly willing that his Lordship should keep his charities to himself if those in any way interfere with him in his giving us proper wages. We ask no charity, but proper wages for a proper day's work. If our wages are reduced because of these schools, hospitals, and cottages we do not see them in the light of charities at all, but part of our proper wages. We have also to remark that in the way of low rent, cottages and land, we believe that it will be found out that the Llanberis men in this respect are better of than us, and certainly in the way of better wages they are greatly in advance of us." Bargain letting in the quarry had for years been a farce and the workmen were forced to accept the terms of the bargain-setter no matter how unreasonable they might be.

After protracted negotiations the men returned to work on September 17 under the Pennant Lloyd Agreement, so called after Pennant Lloyd, the estate agent, who interviewed the men on behalf of Lord Penrhyn. The men gained many substantial concessions, including recognition of the Union, fair terms of letting bargains, and what amounted to a minimum wage of 27s. 6d. a week for quarrymen. When the men attended at the Quarry on September 17 it soon became clear that the manager did not mean to act upon the terms of settlement agreed upon and so they came out again on strike the following day. The matters in dispute were submitted to arbitration ; the decision went against the management, who were obliged to resign, and so work was again resumed at the Penrhyn Quarry on November 9, after a stoppage of work lasting fourteen weeks. The Pennant Lloyd Agreement was put into operation and it was in many respects the Magna Charta of the Welsh quarrymen.

1874 was a historic year in the history of industrial relations in the industry. The North Wales Quarrymen's Union was founded and recognition was won for it after disputes in the largest quarries in the world. The major reason for the success of the quarrymen was the very great prosperity in the trade ; demand for slate greatly exceeded supply, and prices were advancing rapidly and so stoppages of work meant serious losses to owners. The quarry proprietors would not co‑operate in a concerted attack on the Union and the quarrymen lock out or on strike readily found work in other districts. These prolonged disputes did, however, restrict production at a time when demand was increasing rapidly and adversely affected the prospects of the industry both by encouraging the use of substitutes and by frightening away the investor.

Aspects of the Slate Industry 20: The Expansionist Period 10

Quarry Managers' Journal January 1945

First series

Second series

Third Series

Expansionist period 10

Other slate information

National archive slate records

Links