Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

It is remarkable how certain things perfectly insignificant and harmless in themselves, have always attracted a disproportionate share of attention and led people to indulge either in extravagant praise or in scathing criticism. One of the best instances of phenomena of this description is the method generally used by Welsh quarrymen to distinguish different sizes of slates. On the one hand we have the biting comments of Mr. Briggs, of Oxford, in his "Short History of the Building Crafts." He writes that "Among all the anachronisms and stupidities connected with the terminology of modem building, there is nothing to compare with 'Duchesses,' 'Rags,' and 'Large Ladies'." If Mr. Briggs resorted to such trenchant criticism against the interesting custom of calling certain sizes of slates by such colourful names as 'Duchesses' and 'Ladies,' what devastating remarks would he, I wonder, have made after contemplating the picturesque and suggestive titles as recorded by R. Holme in his "Academy of Armoury," 1688-which were used to distinguish different sizes of stone slates in the seventeenth century? At that early period one size of stone slate was called 'Jenny Why Gettest Thou,' another size was called 'Rogue Why Winkest Thou.' Admittedly, one would feet rather foolish and self-conscious when ordering a thousand 'Winking Rogues,' but on the other hand, to order a thousand 'Countesses' or 'Duchesses' gives one a flattering sense of masterfulness and power, as well as lending dignity and prestige to an otherwise very ordinary commercial transaction.

It does set one off wondering why English stone slates were called 'Winking Rogues' and 'Getting Jennys' in the seventeenth century; the only two sizes of Welsh slates produced at that time were called 'Singles' and 'Doubles'; later on, as has been mentioned above, we-have 'Duchesses,' 'Ladies,' and so forth. Why this intriguing preoccupation with women, love and the married state? Why introduce effeminate things into a thoroughly tough and masculine occupation? Is this a problem which can only be solved by the modem psychologist with his formidable array of Repressions, Sublimations, Rationalisations and the rest of the gadgetology' of this over-rated science? As a matter of fact, the economic historian can answer the question in his usual prosaic and simple manner - except for the 'Getting Jennys' and 'Winking Rogues' probably those were invented by a humorist and their use was confined to the highly-localised area where stone slates could be produced from fissile lime-stones or sand-stones, The system of nomenclature which incurred the displeasure of Mr. Briggs .in the 'twenties of the present century, actually inspired Mr. Leycester, who was a judge on the North Wales circuit in the 'twenties of the last century, to compose the following poem after a visit to the Penrhyn Quarries; it is reproduced in full as it deserves a better fate than to be thrown among the limbo of forgotten things.

" It has truly been said, as we all must deplore,

That Grenville and Pitt made Peers by the score;

But now 'tis asserted, unless I have blundered,

There's a man who makes peeresses here by the hundred ;

He regards neither Grenville, nor Portland, nor Pitt,

But creates them at once without patent or writ.

By the stroke of the hammer, without the King's aid,

A Lady, or Countess, or Duchess is made.

Yet high is the station from which they are sent,

And all their great titles are got by descent;

And when they are seen in a palace or shop,

Their rank they preserve and are still at the top.

Yet no merit they claim from their birth or connexion,

But derive their chief worth from their native complexion.

And all the best judges prefer, it is said,

A Countess in blue to a Duchess in red.

This Countess or Lady, though crowds may be present,

Submits to be dress'd by the hands of a peasant;

And you'll see when her Grace is but once in his clutches,

With how little respect he will handle a Duchess.

Close united they seem, and yet all who have tried them,

Soon discover how easy it is to divide them.

No spirit have they, they are thin as a lath,

he Countess wants life and the Duchess is flat.

No passion or warmth to the Countess is known,

And her Grace is as cold and as hard as a stone;

And I fear you will find, if you watch them a little,

hat the Countess is frail, and the Duchess is brittle;

Too high for a trade, without any joke.

Though they never are bankrupts, they often are broke.

And though not a soul either pilfers or cozens,

They are daily shipped off and transported by dozens.

In France, Jacobinical France, we have seen

How thousands have bled by the fierce guillotine;

But what's the French engine of death to compare

To the engine which Greenfield and Bramah prepare,

That democrat engine, by which we all know

Ten thousand great Duchesses fall at a blow.

And long may that engine its wonders display,

Long level with ease all the rocks in its way,

Till the vale of Nant Ffrancon of slates is bereft

Nor a Lady, nor Countess, nor Duchess is left."

Acting on the assumption that this felicitous piece of poetic tomfoolery has sufficiently stimulated the interest of our readers in this matter, we will proceed to give a brief account of the manner in which this unusual method of differentiating slates came to be adopted throughout the Welsh slate districts. (Lest a reader with an inquiring turn of mind should send in an S.O.S. in next week's "Correspondence" for a description of "the democrat engine" invented by Greenfield, who was manager of the Penrhyn Quarries at that time, and his collaborator, Bramah, who, despite his eastern sounding name, was an English engineer, let us at once announce that we ourselves are somewhat mystified. It is variously described as "a powerful press" and as "a kind of screw for wrenching slabs from the rocks"; apparently it was of little practical value, because, after the death of Greenfield in 1825, we hear no more about it).

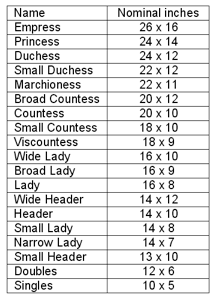

Sizes of Slates As early as 1557 we find that only two sizes of Welsh slates were produced, namely, 'Singles' measuring 10ins. by 5ins., and costing 1s 8d per thousand, and 'Doubles,' measuring 12ins. by 6ins., and costing 2s. 8d. per thousand ; 'Doubles' were neither twice as dear, nor twice as large as 'Singles,' so that as, far as we can infer to-day, they were called 'Doubles' simply because they were larger than 'Singles.' With the expansion in the market for slate and an improvement in the craft skill of the quarrymen, larger sizes of slate were introduced and these were differentiated in the following manner: the smallest size was called 'Singles,' the next size' was called 'Doubles,' the third size was called 'Double Doubles,' and then 'Double Double Doubles,' 'Double Double Double Doubles,' and so forth. Obviously this was a cumbersome and confusing method, and in 1738 General Warburton, owner of the Penrhyn estate, introduced a new classification: 'Singles' and 'Doubles' were left unchanged, but 'Double Doubles' were now called 'Ladies,' 'Double Double Doubles' became 'Countesses,' 'Double, Double, Double Doubles' became 'Duchesses,' and still larger sizes were dubbed 'Marchionesses' and 'Queens.'

These names are still used by the quarrymen, but the trade describe the slates by their length and breadth.

Such is the origin of the ingenious and unique system of nomenclature which delights us to-day, because of its very quaintness, just as, a little over a century ago, it amused and dignified a judge so much that he left his dry legal tomes to compose frivolous rhymes about it.

Our Quarry Aristocracy: A System of Nomenclature

Quarry Managers' Journal November 1942

First series

Slate aristocracy

Second series

Third Series

Other slate information

National archive slate records

Links

Penrhyn Quarry 1922