Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

The expansionist period in the history of the slate industry may be said to have covered the first three‑quarters of the nineteenth century. This was an epoch of great and rapid growth in the scale of production. The estimated output of British slate increased from 45,000 tons in 1793 the peak year of the boom which immediately preceded the Napoleonic wars ‑ to 504,000 tons in 1877, when the apex of the great building boom in the 'seventies was reached; in the intervening eighty-four years the output had increased more than eleven-fold. The rapidity of this growth will be appreciated when it is pointed out that it was almost equal to the rate of expansion in the coal industry during the same period.

For several years preceding the outbreak of war with France in 1793 the demand for Welsh slate had been in excess of the supply. The war caused the tide of prosperity to ebb as it brought with it an increase in freight rates, insurance upon vessels was increased to 10 per cent., and Welsh slate boats refused to venture further than Milford Haven without a convoy so that the London market was crippled. Building became slack, especially after the imposition in 1794 of heavy taxes upon the more important building materials.

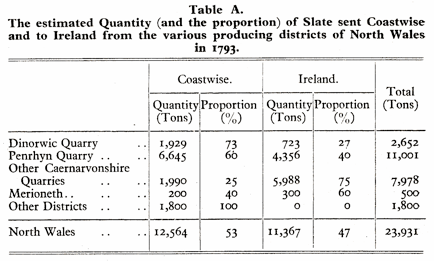

Pitt raised the tax upon plain tiles, which had been subject to taxation since 1784, from 3s. to 4s. 10d. per thousand, and to satisfy the clamant demands of tile manufacturers a 20 per cent. ad valorem tax was levied on all slates carried coastwise. The incidence of this tax was distributed most unequally among the different producing areas; slates shipped to Ireland were free from duty so that in 1794, as is indicated in Table A, little more than half the output of North Wales was affected, whereas practically all the output of Cornwall and Devon was taxed; other districts, such as Leicestershire, could dispatch their slates to market without payment of duty.

The tax was levied upon freight as well as the value of slates, so that the greater the freight costs the heavier was the tax per ton ; on this account the London market for Welsh slate was affected far more adversely than the Lancashire markets, and in the three years following the imposition of the duty, the quantity shipped to London was less than half what it had been in the previous three years, and it seemed as if the slate of Cornwall and Devon was going to regain its monopoly of the markets along the southeast coast. The tax tended to restore the old demarcation of markets among the various slate districts, and to stimulate production in certain areas by providing them with a differential advantage over less fortunately situated districts. The burden of the duty upon North Wales slate became heavier as the rate of tax was progressively raised, and with the decline in the relative importance of the Irish market as an outlet for its products ; there were, however, as we shall see later, compensating factors which more than offset the restrictive effects of the tax and which made it possible for production in this area to expand more rapidly than in any other district.

Within North Wales itself the burden of the tax did not impinge with equal force upon all districts. The Penrhyn and Dinorwic Quarries - the largest concerns in the Bethesda and Llanberis districts respectively - together produced 57 per cent. of the total output of North Wales in 1793; 63 per cent. of their production was shipped coastwise to the new markets created by the Industrial Revolution, whereas the smaller quarries in the Llanberis district and in the contiguous Nantlle district sent only a quarter of their output coastwise and the remainder to the traditional Irish market; the minor slate districts of Denbighshire and Montgomeryshire sent their produce along canals to the English market and evaded the duty altogether.

In the first part of 1794 the coastal trade in Welsh slate was brisk owing to abnormal loading in anticipation of the tax, but afterwards the domestic demand slumped, and the estimated output of Caernarvonshire fell from 23, 130 tons in 1793 to 18,440 tons three years later. It is significant that the whole of this contraction occurred in the Penrhyn and Dinorwic Quarries which were so dependent on the home market. The numerous small concerns in the Nantlle and Llanberis districts which were not so affected by the slate tax, and exported so largely to Ireland, more than maintained the level of their production ; the outputs of these two areas were augmented as the quarrymen who were discharged from the two larger quarries sought a precarious existence by reverting to their old practice of working slate on the commons and co‑operating to, send their produce to the Irish market. In 1797 the Irish demand was reduced to the merest trickle, and the depression became very acute in all districts.

The slate industry from 1796 to 1802 was working at less than half its productive capacity, and the privations of the necessitous unemployed quarrymen almost led to corn riots in 1800 and 1801. The philanthropic efforts of Lord Penrhyn to alleviate the keen distress among his quarrymen, over 75 per cent. of whom were unemployed in 1798, by setting them to improve roads, clear mountain land, and plant potatoes for their own consumption, were short‑lived and on too inadequate a scale to solve the problem of unemployment; his quarrymen complained that they were kept without "subsist" wages for six weeks and his agent was so dilatory in paying the carriers who brought the slate down from the quarry to the quays, that the latter when called upon to pay their rents compared themselves to "the children of Israel when enjoined to make bricks without straw." This depression has rarely, if ever, been equalled in intensity in the history of the industry.

The slump was arrested in 1799 and building became gradually more brisk and was very active from 1803 until 1812. The slate industry enjoyed a fair measure of prosperity until 1814. During the following two years the market became stagnant with prices falling in all slate producing districts. Aggressive selling brought about a radical diminution in profits ; the net receipts of the Dinorwic Slate Company were reduced from 59 per cent. in 1815 to 24 per cent. in 1816, and in the last quarter of the later year a small loss was actually incurred.

In an endeavour to maintain their high customary rate of profits, the Penrhyn and Dinorwic enterprises in 1817 decided to collaborate in the determination of prices ; in this project they could rely upon the active cooperation of the Festiniog Slate Company, which worked the largest quarry in the adjacent Festiniog district, as the controlling interest in that concern was held by two of the Dinorwic partners. In that year, however, building revived and the slate industry experienced a short‑lived boom with its apex in 1891; output fell off in I82o and then increased rapidly to the culminating peak Of 1826. Considerable capital expenditure was being incurred at this time in the erection of mills and factories, and this resulted in feverish activity in the slate industry . It was a period of extravagant speculation in slate quarries, of frequent lawsuits between landowners and lessees, quarry owners and slate merchants and of wide‑spread unrest among the quarrymen who agitated for higher wages. In 1826 the great speculative boom ingloriously collapsed. This financial crisis brought about an immediate recession in building.

It is significant that despite the contraction in building, entrepreneurs in the slate industry were able to raise prices and to increase sales during the year 1826, and even in 1827 the volume of slate production almost equalled that of 1825. It is also significant that the combined profits of the Penrhyn and Dinorwic concerns in 1826 and 1827 were higher even than the very high profits earned during 1825. This boom in the state industry is notable for the co‑operation of the larger entrepreneurs in pursuing a joint price policy. The experience of the Penrhyn and Dinorwic concerns during the post war depression had convinced them that it was to their mutual advantage to co‑operate in the control of prices, and the price leadership assumed by these two concerns has been one of the most important features of the industry on its marketing side.

The building depression in the late twenties was too severe and prolonged not to have an adverse effect upon the slate industry, despite the increasing popularity of its product. At the end of 1827 all quarries were carrying heavy stocks of slate and entrepreneurs were constrained to reduce their output progressively. The break in slate prices came in July, 1827, and they fell progressively until the Spring of 1831. The volume of production, however, began to recover slowly as early as 1828 but for several years the industry worked very much below its full productive capacity.

At this juncture the quarry proprietors began to organise protests against the slate tax. The latter had been gradually increased from 20 per cent. ad valorem in 1794 to 35.2 per cent. in 1809; it remained at that exceptionally high level until 1814, when, the war duty having expired, it was reduced to 26.4 per cent. In 1823 the duty was levied by weight or tale instead of on the former ad valorem basis, and the net result of this change was a slight increase in the burden of the tax upon Welsh slate in the Lancashire and Midland markets and a substantial diminution in its burden in the case of the more distant Scottish and London markets.

An anomalous situation had long existed under the slate duty because all ports included in the jurisdiction of each Collection of the Customs were regarded as one port, so that within each of those areas slates could be carried coastwise free of duty. In the latter half of 1828 it was declared by Treasury Order that Preston, as well as Ulverston, was within the port of Lancaster, with the result that Westmoreland and Lancashire slate could be shipped free of duty from Ulverston to Preston, which was linked up by a canal system with the Midlands. The slate producers of the Lake District were now placed in a stronger competitive position and so the Welsh entrepreneurs redoubled their efforts to secure either the abolition of the slate duty or, at any rate, the removal of the gross inequality in its incidence ; several meetings of persons interested in the industry were held to consider "The unprecedented depression of the Welsh Slate Trade, and the propriety of petitioning Parliament to have Wales put upon an equality with England and Ireland as regards the duty affecting it."

Fortunately for the industry, Althorp in 1831 decided to repeal the duty on sea‑borne coal, and as the slate tax had been collected by the same revenue officials it was decided on grounds of economy to dispense with it as well.

"The effect of the repeal was soon evident in the great increase in the use of that sort of roofing. Tiles, weighted with duty, could no longer hold their own against slates, and the dull grey began to usurp the place of the lively red and rich brown roof in our country scenery" ; so writes Dowell in his "Taxation and Taxes in England." Tile producers complained that their product was being ousted from the market, and in 1833 they succeeded in getting the duty on tiles repealed. The rate of expansion in the slate industry during the 'thirties was remarkable and the output in 1840 was more than twice what it had been ten years earlier.

Aspects of the Slate Industry 11: The Expansionist Period 1

Quarry Managers' Journal March 1944

First series

Second series

Third Series

Expansionist period 1

Other slate information

National archive slate records

Links