Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

Historical aspects of the Welsh slate industry

D Dylan Pritchard MA FSS

I think it was Bacon who said, in one of his essays, that "Houses are built to live in and riot to look on." This dictum is true so far as it goes, but like every half truth, it does not give a complete account of the true state of affairs. In the inter war period people were almost as much concerned with the external appearance of houses as with their internal planning. It would be exaggeration to paraphrase Bacon and say "Houses are built to look on and not to live in," but it is reasonable to assume that if he was our contemporary he would have modified the wording of the sentence and written "Houses are meant to live in as well as to look on."

The memorandum recently submitted by the North Wales Quarrymen's Union to the Welsh Reconstruction Advisory Council, and which has been extensively reproduced in our previous articles, draws attention to this development and emphasizes its significance for the roofing material industries.

Building - Unplanned

Throughout the nineteenth century urban areas were developed intensively and houses were huddled together in mean, narrow, streets. The working classes were housed as close as possible to the factories and docks where they worked. Little regard was paid to civic planning. The commercial instinct prevailed. Economic man reigned supreme. The average town dweller had neither time nor inclination to think about the appearance of his house. "Houses are built to live in and not to look on." Economic man cared little about the appearance of his roof. Indeed ' he probably had never even seen his own roof, although, from his bedroom window, he might have noticed his neighbour's roof across the street. In those days one only became aware that one's house had a roof on the rare occasions when it sprung a leak; only when it became an infernal nuisance did the roof succeed in obtruding itself into one's consciousness. In those halcyon days it may easily be understood that the appearance of a roof was of minor importance, all the emphasis being laid upon cheapness, durability and reliability so that flat pitched roofs of purple Welsh slate were the order of the day. During the nineteenth century, as Professor Clapham has told us, "Slate, easily distributed from Wales or Westmorland, had become the symbol of progress."

Building - Less Unplanned

On the other hand, during the present century we have become progressively more roof conscious. The accelerated centripetal growth of our large towns; the unparalleled expansion of suburban areas on less intensive lines; the octopoid, almost uncontrolled, growth of ribbon development; the prevailing craze for detached and semi detached houses; the greater insistence on front and back gardens, green trees and open spaces; the greater width of streets and pavements; the popularity of low two storey houses as compared with the much higher buildings common in the Victorian era all these factors have combined to make us cumulatively more roof conscious. Now that roofs can be seen from the front and back gardens and from the streets, the suburban dweller has become more roof conscious with the result that greater attention is paid to their appearance both by the impressionable public and by the professional architect and builder.

This growth of roof consciousness led the town dweller to demand a roof which suited his taste or lack of taste. He wanted a "modem" roof for his "modern house." Slates, like antimacassars and china dogs, he considered to be old fashioned, Victorian, outmoded and ugly. He objected, upon what he fondly imagined to be aesthetic grounds, to the purple and blue grey slates of Wales. He wanted something more colourful, picturesque and smart. The result was that a tremendous demand was created for the more flashy type of roofing materials. The output of clay roofing tiles increased from some 200,000 tons in 1912 to about 1,200,000 tons in 1935, whereas the output of roofing slates fell contemporaneously from 378,000 tons to 303,000 tons.

Many of us are fully aware of the rich potentialities of slate as a roofing material, but town dwellers know very little about its merits. Travelling upon the upper decks of tramcars and in railway carriages they have caught glimpses of ugly, dirty, dilapidated, low pitched slate roofs, set out in monotonous, interminable rows. They have noticed that all the slums which were demolished in pre war days, and which have been blown down by enemy action since, were roofed with slates, and, possibly (though I do not wish to overstress this point), have come to associate slates with slums. The man in the street knows nothing about the relative merits and demerits of slates and tiles, but he increasingly favours the latter because, in his opinion, they are brighter, smarter, and more fashionable.

The Roof Beautiful

Tile manufacturers fully realize how important a selling point is the warm and varied colour of their product. The June issue of our contemporary - The British Clay Worker - contains an article upon "The Roof Beautiful" written by an architect, and the following quotations from it should interest slate producers. "Given a free choice and some aesthetic appreciation, there can be little doubt that a tile roof would be preferred by nearly all house owners. This can be said without fear of contradiction. It is not always realised, however (even by tile makers), how far aesthetic considerations enter into this judgment, and, rightly encouraged, favours their products. Evidence of this preference sometimes takes queer forms as, for instance, where posters which endeavour to persuade intending visitors of the beauty of some resort, translate roofs of buildings which are uninterestingly slated into glowing surfaces of weathered tile. Perhaps the only class in which a general preference for clay tiles on aesthetic grounds should not be given are such special instances as in the stone slated villages of the Cotswolds." The author, who, one is led to suppose, is unaware of the fact that roofing slates are still being produced, goes on in the following vein: "It is hardly for me to tell tilemakers how they should set about their business from the technical side, but I may perhaps be permitted to express, as forcibly as I can, a request that they should devote more attention than has sometimes been the case to the aspect of their wares which constitutes the chief claim to supremacy good colour free of "faking" and surface texture which will "weather" well. Architects have no use for the purplish, semi glazed, sharp edged kind of tile which has been likened to "a slab of boiler plate painted pink." So I say, push on, ye tile makers, and give us good stocks of genuine well burnt un-faked, tiles which will stand up to the weather and improve yearly. And heed the desire for surface texture and agreeable colour, yet who produce machine made tiles: exclude the raw tones and glistening surfaces which grow shabby, but never mellow." Tile manufacturers will not fail to take this exhortation to heart and will exploit to the full the differential advantage which they enjoy in this respect over the manufacturers of most competitive roofing materials.

Green and "rustic" slates are still very popular although their cost is excessive compared to that of other kinds of slate; this kind of slate, which is chiefly produced in the Lake District and in Cornwall and Devon, forms a very small proportion of the total output and it is extremely difficult to increase the supply. The recently formed English Slate Association includes all the manufactures of green and rustic slates and, when the post-war building boom gets under way, it will experience little difficulty in pushing the sales of these types of slates. Indeed, the major difficulty which the English quarries will have to face in post war days will be how to increase production quickly enough to supply the demand. The author has inspected some of the more important English quarries during the past year, and was greatly impressed by the foresight shown by the proprietors. In one famous quarry the production of roofing slate had been stopped completely and all of the depleted labour force was, as a matter of policy, engaged upon the opening and development of the slate vein so that, after the war, production could be increased quickly and smoothly. This policy may be contrasted with that of some Welsh quarries, where now, as in the last war, unproductive work has been cut down to a minimum and only the best slate rock is being worked so that, when the post war boom materialises, there will be great difficulty in increasing the volume of production.

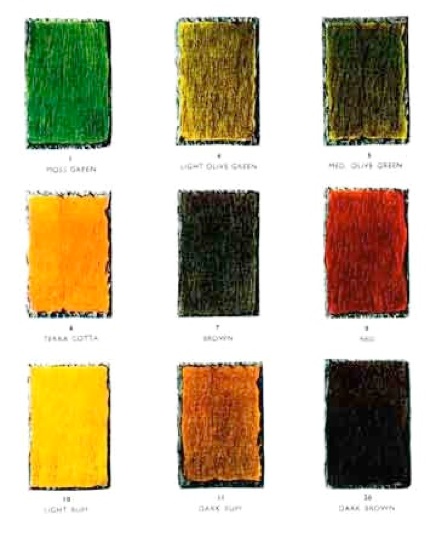

Colloidal slate colours

Colloidal Slates (more ...)

It is reasonable to conclude that the marketing difficulties of the Welsh quarries will be much greater than those of the English quarries, largely because of the prevailing preference for colourful roofing material. The realisation of the importance of the aesthetic factor led to the exploration of the possibility of artificially colouring the natural roofing slate. A few years ago a secret "Colloidal Process" was discovered by which it is possible to colour slates with permanent tints. Tests of immersions in boiling concentrated acids and alkali, repeated immersion in concentrated sea water, application of the strongest solvents and removers of paints and varnish, tests at red hot temperature and by freezing, have shown that the colours are absolutely fast and cannot be removed. A great feature of the process is that it does not obliterate the natural grain and texture it is not in the least like a thick enamel coating. Slates can be coloured by the process to very many shades or to special shades desired by architects. The shades supplied are soft in tone and do not look garish. The varieties on the market before the war were several shades of green, brown, buff and also terra cotta and red, and experiments were continually going on with a view to producing a wider range of permanent tints. Shortly before the war the extra cost of a colloidally coloured slate roof varied from three to six guineas according to the size of the house. In 1937 in the London district the average all in cost of roofing per square yard with natural Festiniog slate was 7/-, with colloidally coloured slate 8/-, and with green Westmorland slate 10/6; these statistics show that the extra cost of colouring slates colloidally is small, and that the colloidal slates are substantially cheaper than the popular, but very expensive, natural green slate.

Colloidal slate would seem to be an ideal roofing material for present day needs, inasmuch as it combines the advantage of being a natural rock product of proved maximum durability and minimum maintenance, with the added advantage of being obtainable in a wide range of colours a most important consideration in this roof conscious age. Putting a new product of this kind on the market involves very heavy advertising costs, the maintenance of an expensive laboratory to carry on research, and the setting up of an expensive plant capable of turning out a fairly large output. The capital resources of the concern which originally sponsored the production of colloidal slates was wholly inadequate, but it was taken over, about six or seven years ago, by the Oakley Slate Quarries Companies, Limited, which, before the war produced annually some 22,000 tons of natural roofing slate, and has an authorised capital of £365,000.

No colloidal slates are being produced at the present time the materials and the labour cannot be spared for what at the moment are non essential processes. Needless to say, it is intended to resume production as soon as possible.

Only a very minute proportion of the produce of the Welsh slate industry was coloured by the colloidal process before the war, and it is obvious that such will be the case after the war also although a considerable expansion in the demand for colloidal slates may reasonably be anticipated. Much the larger portion of the Welsh product will have to be sold in its natural colour and the industry must go in on a large scale for what the Americans call "consumer training”. It is not too much to state that the future prospects of the Welsh slate industry prosperity or depression, good profits or no profits, expansion or contraction largely depends upon how this problem is tackled. In future articles we propose to suggest ways and means by which this problem may be dealt with.

Aspects of the Slate Industry 4: Roofing Fashions

Quarry Managers' Journal August 1943

First series

Second series

Roofing fashions

Third Series

Other slate information

National archive slate records

Links

Arts and Crafts roof North Wales